A history of: Chiloquin… The Lumber Mills… The Railroad… The Water…

Most of this history comes from the Klamath Watershed Partnership publications and from articles and anecdotes collected by The Friends of the Chiloquin Library and published in their 3 volumes of History & Recipes books.

Chiloquin…

The first white men to arrive in the area were envoys of the Hudson’s Bay Fur Company, who reached the confluence of the Sprague and Williamson rivers in the fall of 1826. Led by Finan McDonald and Thomas McKay, the group traveled south from the Columbia River in search of fur trapping locales. Later that fall, Peter Skene Ogden arrived near Chiloquin and traded with the Indians, securing foodstuffs to keep his party alive until spring. They camped near the present site of Collier Memorial State Park.

A campsite for a group of Klamath Indians became known as Camp Chiloquin, the white settler version of Chay-lo-quin, the name of a respected war chief who was alive at the time of the treaty of 1864. Camp Chiloquin was a few shacks and tents scattered over a wide field at the confluence of the Sprague and Williamson rivers. Since Chiloquin was on the reservation, in order for white settlers to obtain land, they purchased Indian allotments. The first allotments were sold in 1918. Before allotments became available an Indian Trading Post, consisting of store, hotel and livery stable, was begun by the firm of Clepper and Moore, the location leased from the Indians.

The Klamath Indian Agency was established in 1868 and served as reservation headquarters until termination in 1954. It is located on Hwy 62, about 6 miles south of Ft, Klamath. It was built at that location because it was near Council Groves, the site of the 1864 treaty signing. Located on 80 acres, the Agency was a self-sufficient community with its own water, electricity and telephone systems. It originally had 100 buildings, including hospital, fire station, police force, school and gas station.

Chiloquin began to develop as a town in about 1910, when the railroad was built north from Klamath Falls to Kirk, a few miles north of Chiloquin, and now a ghost town. Chiloquin Mercantile and Chiloquin Warehouse were the pioneer businesses of the town. The first Post Office was established in 1912. The first movies were shown in the warehouse, where the audience sat on bales of hay and the picture machine was powered by an automobile engine. The daily trip of the train from Klamath Falls to Kirk and back was a leisurely affair with the engineer stopping anywhere along the route with usually several stops along Upper Klamath Lake to pick up fishermen. The train was even known to wait for the last catch to be bagged.

A one room school took care of the children’s educational needs until 1918, when the school expanded to two teachers. In the 1920’s Chiloquin’s elementary and high school districts were formed, and construction began on a school to house both the grade and the high schools. Finished in 1926, the last 2 years of high school were offered for the first time.

The first electricity was brought in by Copco in 1920 and the water works company begun by A. C. Geinger in 1924 was sold to the City after it incorporated. The town was plotted by Henry Stowbridge, L.B. Robinson and Mary Jackson to the east of the Williamson River. By 1928 the City of Chiloquin included a townsite originally plotted from Indian lands and known as the Juda Jim Allotment, all of which lay east of the Williamson River. The west side, known as West Chiloquin, was developed and sold by R. C. and Alice Spink. Clyde’s Market, still in operation today, was originally Spink’s Market.

The city was incorporated on March 9th, 1926, the only city to be incorporated on an Indian reservation. On election day the town went wild. Everyone came to vote, some even carried in on stretchers. Two hundred more votes were cast than there were adult citizens in the community, and around $10,000 changed hands as election bets were lost or won. A.C. Geinger was elected mayor, and a new city council set up. Although none on the council had ever before been connected with municipal works they drafted the laws for the new city. At that time there were 2,000 inhabitants, 3 big lumber mills, box factories, restaurants, barber shops grocery stores, doctors, dentists, a lawyer, drug store, pool hall, movie theatre, dress shop, shoe store, roller rink, taxi service, dance and pool halls, and in 1927, a bank. Unlike today, residents rarely had to make the trip to Klamath Falls.

Chiloquin became a boom town, known as “Little Chicago” because of its rough reputation. Made up of loggers, mill workers, ranchers and Indians, most nationalities were represented, including the Chinese. One of the main problems was the keeping of law and order.

Between 1923 and 1929 a building boom hit Chiloquin. One of the first acts of the new city administrators had been to create a fire zone in the business district and after fire destroyed many of the unsightly wooden frame buildings in town in 1926, property owners were forced to build fire-proof structures. A.C. Geinger and his son Roy constructed a 2 story brick General Store, which is still the family-owned Kircher’s Hardware store of today, although the top story has gone – burned in 1958, when a young boy, feeling cold, lit a fire on the upstairs wooden floor. Henry and Josephine Wolff built a brick building across from Geinger’s to house their bakery. Three more blocks of brick buildings were completed, ending with the Markwardt Bros. Garage, which opened in the summer of 1929, replacing their first garage, built in 1922.

Many of the streets were named after Klamath and Modoc Tribal names – Chiloquin, Chocktoot, Lalo, Schonchin, Wasco and Winema were all prominent tribal families. Yahooskin Street was named after the Paiute tribe Yahooskin, Band of Snakes. Lalakes was named after Klamath Lake. Blockinger street was named for the Blockinger Lumber Mill and Box Factory.

The actual city limits of Chiloquin have grown since its incorporation in 1926. At first, due to a surveying error, Chiloquin consisted of just the downtown area. The northeast section was annexed on 1929, the southernmost section annexed in 1947, the westernmost section annexed in 1954, and finally, the northwestern section annexed in 1958.

The closures of the lumber mills, the Great Depression and a series of disastrous fires had a major effect on Chiloquin. The industry of the area was badly impacted by the demise of the timber mills. When the mill in town closed in 1988, it left widespread unemployment. Aside from ranching in the outlying areas, there is no major industry at the present time. The 3 major employers in the area are Jeld-Wen (windows, door frames), Klamath Tribes (management, health services), and Klamath County Schools.

Now, within the city you will find two small food markets, two eating establishments, a medical center, hardware store, book store, library, Post Office, beauty shop, art gallery and a large non-profit Community Center. Schools within the city limits are an elementary and high school. There are several different denominations of churches and it is also the home of the Klamath Tribes Administration, and the Klamath Tribal Health Center. A volunteer fire department and a volunteer ambulance service are based in the city. For everything else, residents make the 30 mile trip to Klamath Falls.

The Spanish Castle

A few civic minded women in Chiloquin started a Women’s Improvement Club in the early 1920’s. From 1924 to 1926 the women earned nearly $8000 by giving dinners, dances and other enterprises. 1926-27 they built a large club hall in West Chiloquin, which they also used for dances. Following the onset of the depression, the club dissolved and the building lost through the failure of a loan company.

For a while it was used as a shooting gallery, and after several years, was moved to the east side of Chiloquin by Art Priaulx, Chiloquin Review Publisher. The ‘Review’, established in the summer of 1925 covered the entire northern section of Klamath County, giving readers the local and county news. Once the building was moved, Art renamed it the Spanish Castle and operated a dance hall. Next it became a skating rink, and during the war years, the National Guard used the building for target practice. After the war, around 1950, it became the V.F.W. Hall. Later the Masons bought the building and the Cascade Crest chapter of the Eastern Star held meetings and functions there. When that chapter disbanded the building was given to the City, and the Winema Grange took care of the building, using it for their meetings and functions. Finally, during the earthquake of 1993, the building was damaged beyond repair and had to be destroyed.

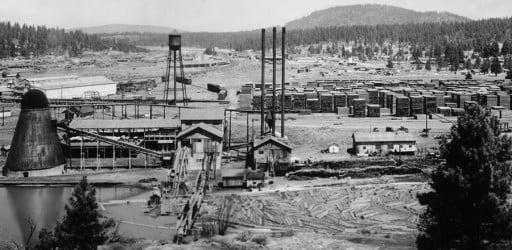

The Lumber Mills

Beginning around 1910, the lumber industry experienced rapid growth and lumber products became the lifeline of the Chiloquin area. In 1916, Wilbur Knapp built a small circular sawmill, the Modoc Lumber Company, on the Williamson River, about a mile and a half north of Chiloquin. In 1924 the mill was sold to the Forest Lumber Company from Kansas City, who built a large mill and changed the name to Pine Ridge. By 1928 the mill was manufacturing 250,000 feet of lumber per day. In 1939 the mill burned to the ground in the Pine Ridge fire, and was never rebuilt.

Meanwhile, in 1919, John Bedford and Harold Crane built the Sprague River Lumber Company on the Sprague River, 3 miles east of Chiloquin. Sold to William Bray in 1921, it became the Braymill White Pine Lumber Company, prior to closing in the 1928 stock market collapse. Although closed, Bray allowed some of the work crew to remain in the company houses during the depression.

In 1918, E.A. Blockinger and his son Arthur founded the Chiloquin Lumber Company and Box Company on the bank of the Sprague River, near it’s confluence with the Williamson, in what is now within the city limits. By 1928 the mill was manufacturing 150,000 feet of lumber per day. The Box Factory burned in 1947, and the mill became the Chiloquin Mill, owned by the Salvage Brothers. Purchased by Ernest DeVoe and J. R. Simplot in 1955, Simplot obtained full interest in 1962 and changed the name yet again, this time to Simplot Lumber Company. When it was sold to the DiGorgio Corporation in 1969, the mill operated under the name of Klamath Lumber Company before being changed to D. G. Shelter Products. Finally, in 1977, the plant was sold to a group from Bend, and was renamed Chiloquin Forest Products. It remained operational until 1988. The last operator of the mill site, filed for bankruptcy in 1991, and Klamath County took ownership of the site, through foreclosure, in September 1998. In April 2005, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality authorized remedial activities to be performed at the site. Asbestos containing material was removed from the boiler house and the boiler house was demolished. Approximately 360 tons of petroleum contaminated soil and 530 tons of PCP contaminated soil were transported to off-site landfills. Following the remedial action, widespread dioxin contamination was discovered in the soil remaining at the site. In 2006, a protective cover and deed restriction were selected as the cleanup alternative for the dioxin contaminated soils at the site. The soil cap was constructed on the site in July 2007.

The Railroad

The city of Klamath Falls (originally known as Linkville) had long desired a railroad, and when the Southern Pacific Railroad completed its line into town from Weed, California, in 1909, the citizens went wild with celebration. Chiloquin’s new $5000 depot opened on August 12th 1912, with twice daily trains schedules between Chiloquin and Klamath Falls. By 1915, 40 trains/day operated by six railroad companies, passed through to Kirk, the end of the line, a few miles north of Chiloquin. Daily shipments of around a million and a half board feet of logs were made over the Southern Pacific Railroad to Klamath Falls.

Robert Strahorn formed the Oregon, California & Eastern Railroad in 1915, and after a series of complications and slow construction, the railroad to Sprague River was finally completed in 1923. This new line opened up vast new stands of timber to harvesting, and in many cases loggers had already accumulated huge decks of logs adjacent to the grade before any rails had been laid. By the summer of 1923, the OC&E railroad was delivering 40 carloads of logs per day to the SP Line for shipment to sawmills. The following summer, Strahorn boasted that his railroad was handling around a billion board feet of lumber each month. Today much of this railroad line from Klamath Falls to Sprague River and beyond to Bly has been removed. The remaining railroad bed was converted to the OC&E Trail, an Oregon State Park.

In 1926, Southern Pacific completed the line over the Cascade Range to Eugene. In the years before the construction was begun, large survey crews were on the job and needed many horses for riding and pack teams. R. C. Spink took in hundreds of wild Indian range horses on debts at his general merchandise store, and hired men to break them. The Spinks daughter recalls that she spent most of one summer watching amateur rodeos as the horses were broken to ride and quickly sold to Southern Pacific.

By 1941, Chiloquin had 26 daily trains shipping 90 cars of forest products outbound, 100 cars of sheep and 2500 cars of cattle. Chiloquin was the trade area for the entire northern section of Klamath County serving Ft. Klamath and the Klamath Agency as a mail and freight distribution point. It was a shipping point for the vast Indian Reservation and for a great expanse of land east of the town along the Sprague River.

The Water

When the Klamath Indian Reservation was first created, only Indians could graze on the Indian land, but with the passing of a federal law known as the Dawes Act, many of the restrictions on non-Indian use of reservation grazing lands were relaxed or eliminated. As the nineteenth century ended, more and more non-Indians were leasing allotments on the reservation. Most of the reservation was not fenced, providing little control of livestock numbers and resulting in an increase in the number of sheep and cattle. The range immediately adjacent to the reservation experienced very heavy grazing pressure nearly year-round. When agriculture was being introduced into the area, a number of weirs were built across the Sprague River creating diversions to flood irrigate the pastures and hay ground later in the season. All of these weirs were washed out over time with heavy flood waters.

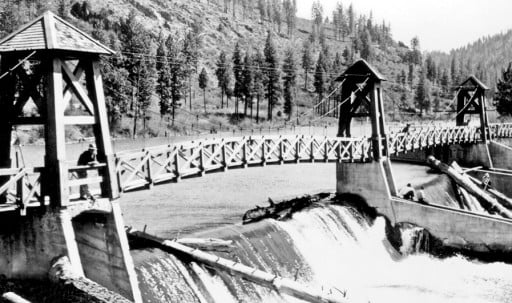

The Chiloquin Dam (also known as the Sprague River dam), located about a mile above the confluence with the Williamson River, was constructed in 1917 to control diversion of water to Modoc Point. When the Klamath Indian Reservation was terminated in 1954, the dam, its canal, and the Modoc Point irrigation project were transferred to the Modoc Point Irrigation District. Historical evidence suggests that fish populations were different from those which exist today. The construction of the Chiloquin Dam interrupted normal fish passage, and non-native fish species were introduced. The major concern now is for native fish species, in particular the Klamath largescale sucker, Lost River Sucker, and shortnose sucker (the latter two are Federally listed Endangered Species), redband trout and two currently extinct species—chinook salmon and steelhead trout. Fish and Wildlife Service, in 1988 estimated that the Chiloquin Dam eliminated 95 percent of the historical spawning runs. The dam was finally removed in the summer of 2008, by which time it was in poor condition. It was replaced by a pumping station further downstream on the Williamson River, to divert water to the Modoc Point Irrigation District.

In the book “Stories Along the Sprague” Buddy Parazoo says “up at the old Sprague River dam we literally had to kick the (bald) eagles in the ass to get down to the river….below the dam the water would overflow the banks, so there would be a few inches of water full of fish….so the eagles were there, concentrated at the dam, hundreds and hundreds of them…..the government used to pay us to shoot them… They paid us up to 1957, five dollars apiece….nowadays they’ll throw you in prison. Isn’t that funny? The mullet runs were amazing in those days…They’d be backed up from the dam….to …the house there on the corner of 97. They were like a log jam waiting for their turn to get up the river.”

During the 1950s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began a program of channelization along the Sprague River and West Sprague River watersheds. There is very little information available about the channelization but local citizens who were involved with the construction, have indicated that this occurred at a time when flood control modifications were taking place throughout the western states. This wave of flood control construction stemmed from passage of a National Flood Control Act in 1936, which authorized and funded the Corps of Engineers. Actual implementation was delayed due to World War II, but after the war was over, the Corps of Engineers made major modifications in a relatively short time. There were major floods in the region, in 1950 and again in 1964 and officials at the Corps of Engineers have indicated that the structures were likely built under an “emergency authorization,” which would mean that little or no planning or documentation of construction activities would have been required.

A long-time resident in Bly, Butch Hadley, worked on the dredging and diking of the Sprague River. He explained that the Corps of Engineers was also conducting willow removal, in order to “conserve” water for agriculture, without realizing the impacts on the stream banks and eventual erosion. In the book, “Stories Along the Sprague” Helen Crume Smith says “There used to be willows all up and down Sprague River. Now all the willows are gone….There used to be wild roses and all different kinds of flowers and plants and grass, but those willows were just huge and beautiful. We made our spears and our bows and arrows and all that out of those willows. My first fishing pole was a willow….There used to be trees – big, beautiful trees on both sides of the river, huge Poderosa Pines….I can see Sprague River like it used to be, so, so fabulous, so beautiful. I could tell you how it used to be, but unless you’ve seen it yourself, you really can’t see it through my eyes.”

The spectacular Klamath Basin, once filled with over 350,000 acres of wetlands, shallow lakes, and marshes that hosted seven million migrating waterfowl and thousands of bald eagles, is now a shadow of its former self. Eighty percent of the wetlands have been drained and wildlife populations have plummeted.

The natives of the region drew much of their sustenance from these wetlands, using the plants, mammals, birds and fishes for everything from food to clothing to transportation to shelter. When white pioneers arrived, they too took advantage of many of the benefits of the wetlands, but land-use changes after the white settlers arrived, significantly changed Upper Klamath Lake and its surrounding wetlands. These wetlands would normally help cleanse the Klamath water system but beginning in the 1930s, they were drained for irrigation, agricultural land, and grazing. Streams flowing into Upper Klamath Lake, consequently, act more like drainage ditches, transporting nutrients directly into the lake from Klamath Basin farmlands rather than being filtered first by the wetlands. And at the southern end of the basin, in 1905, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation initiated the Klamath Reclamation Project to convert the lakes and marshes of the Lower Klamath Lake and Tule Lake areas to agricultural lands. As these wetlands receded, the reclaimed lands were opened to agricultural development and settlement. Today, less than 20% of the historic wetlands remain.

At 142 square miles, Upper Klamath Lake is Oregon’s largest fresh-water lake. It is fed by the Williamson and Sprague Rivers and several small creeks and springs, and is the source of the Klamath River, which flows from Oregon into Northern California and out to the Pacific Ocean. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, Upper Klamath Lake naturally contains a high level of nutrients, supporting diverse plant and animal communities. In the last 60 to 80 years, however, the Upper Klamath Lake has become hypereutrophic, meaning its nutrient levels, especially phosphorus and nitrates, have become so high as to promote dangerous levels of blue-green algae, degrading the lake’s water quality and depleting oxygen levels necessary for fish.

Many public and private groups now recommend returning some farmland back to wetlands. Since 1980, the Nature Conservancy has led the effort to improve the health of the Klamath water system. The Nature Conservancy, Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, PacificCorp, the Klamath Tribes, and local farmers have purchased thousands of acres in the Upper Klamath Basin for wetland restoration.

Despite these losses, there are still a million migrating birds that use the wetlands each spring and fall.